Imagine the sight of massive aircraft engines, weighing more than three tons each, gliding smoothly down a production line in a bustling workshop.

At GE Aerospace’s On Wing Support (OWS) quick-turn shop in Lingang, Pudong, Shanghai, this remarkable and bustling scene comes to life every day. Engines move continuously through the facility, from arrival to maintenance and finally departure, being repaired one after another and returned to customers.

In traditional engine maintenance, engines remain stationary at fixed workstations, much like cars being serviced at a car dealership. But at the OWS shop, a moving repair line has brought about big gains in efficiency. This innovation is the result of GE Aerospace engineers’ efforts to improve maintenance efficiency by activating FLIGHT DECK, the company’s proprietary lean operating model.

Challenges with the Traditional Model

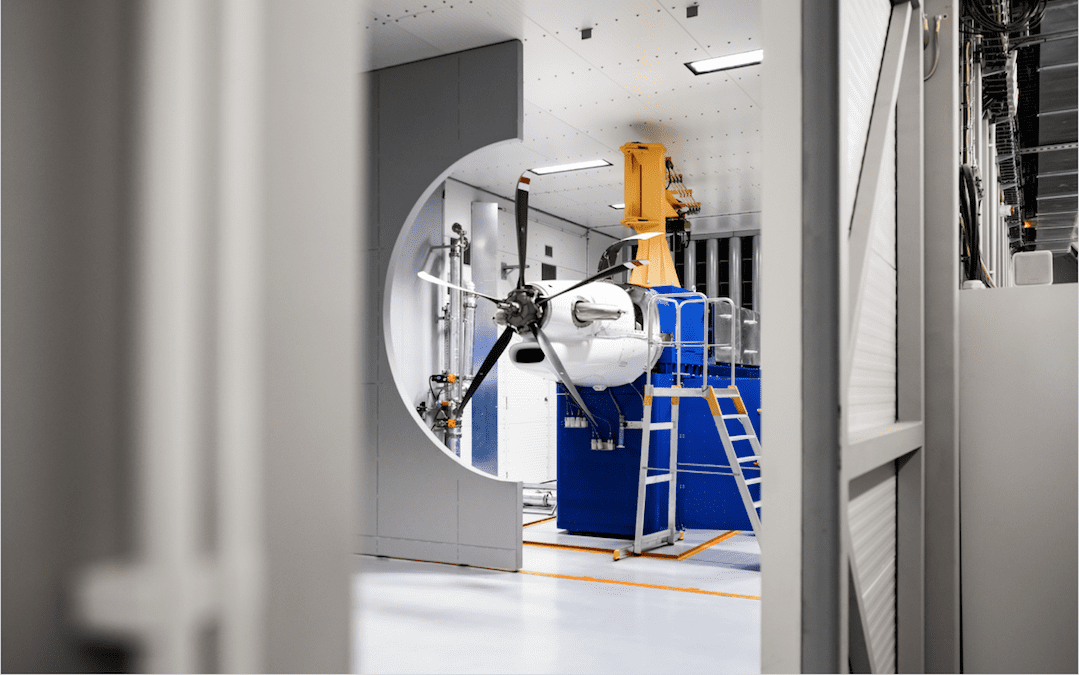

Established in July 2023, the Shanghai OWS facility is the newest of GE Aerospace’s seven global quick-turn sites and the first of its kind in China’s civil aviation industry. It delivers rapid maintenance services for CFM LEAP-1A/1B* and CFM56-5B/7B* engines to customers across China and Asia, handling module repair and replacement for critical components like fans, compressors, combustion chambers, and high- and low-pressure turbines.

Under traditional maintenance methods, each engine entering the shop is placed at a fixed workstation for repair. The process generally involves three steps: disassembly, module repair and replacement, and reassembly. It typically takes 95 days to complete the entire process and deliver the engine back to the customer. However, supply chain disruptions significantly impacted the shop’s maintenance rhythm, extending total turnaround time (TAT) by 47%. The main challenge lies in the “module repair and replacement” phase, in which many core components need to be sent overseas for repair before being shipped back to the Shanghai facility for installation and reassembly. When overseas repair times are prolonged, engines are forced to remain at their fixed workstations, waiting for replacement parts. This not only ties up maintenance tools and keeps engineers on standby but also prevents new engines from entering the shop.

“It’s like sending a ‘sick’ engine to a hospital and placing it in a bed,” explains Wang Tao, the Shanghai OWS site leader. “The doctors use tools and the appropriate medicine to treat the patient. But when the medicine doesn’t arrive, the engine becomes like a patient waiting for medication, stuck in bed indefinitely. Doctors and tools are also tied up at the bedside. With limited beds available, the result is that uncured patients can’t leave and new ones can’t be treated.”

“In the first quarter of 2025, we had a backlog of LEAP engines awaiting repair, with others parked for service,” Wang says. “In the end, we weren’t able to meet our projected target.” Faced with the growing backlog of repair orders and anxious airline customers, Wang and his team began to rethink their approach.

Making “Patients” Move: Implementing a Flow Line Approach

How could the Shanghai OWS team prevent the module repair phase from stalling disassembly and reassembly? How could they streamline repairs and increase throughput?

Wang recalls a daring idea from Maintenance, Repair, and Overhaul Vice President Farah Borges: “Why not bring an assembly-line-style flow line into our shop?” With strong support from Global OWS Leader Alexander Henderson, the Shanghai team pioneered a shift from fixed workstations to a “flow line.”

Now engines move through distinct stages — after disassembly, they advance to module repair and, once completed, they “flow” to reassembly. To tackle the module repair challenges, Wang’s team introduced the lean concept of heijunka — a “buffer storage” solution that optimizes floor space with additional engine storage stands to hold disassembled engines while they await parts.

“We added 10 sets of storage tooling for the core module and LPT module,” Wang explains. This allows the team to disassemble up to 10 engines and store them until overseas-repaired parts arrive, at which point they move quickly to module repair.

“It’s like having 10 patients in a holding area waiting for medication,” Wang says. “When it arrives, they’re treated and moved forward together, freeing up beds for new arrivals. This approach is allowing us to meet the needs of our customers.”

These stands were designed and built locally in China, matching the quality of imported units while cutting delivery time by 75% and costs by 67% — further accelerating TAT and reducing costs.

The new process also transformed the workforce, improving the way the team works. Technicians who used to oversee the entire repair process are now more focused on specific phases. The team has also been able to free up other resources across the site to enhance airline customer support and field service. “As efficiency continues to improve, we’ll bring in new talents to the team to build a more structured hierarchy,” Wang adds.

Continuous Improvement Never Stops

After FLIGHT DECK was activated and the fundamentals were applied, the results came rushing in. Almost immediately, TAT quickly increased nearly 40%, and deliveries soared from one engine in the first quarter to nine in the second quarter. The Shanghai team was energized and, with their eyes on the future, they aimed to further reduce TAT in 2026.

Yet Wang’s team isn’t stopping there. While the three main phases — disassembly, module repair and replacement, and reassembly — now flow smoothly, each requires finer segmentation into sub-zones to optimize efficiency and minimize backtracking. The team is actively refining these details to continuously improve the process. For example, the on-site daily visual management boards will also be adjusted in conjunction with the flow to facilitate more efficient and real-time management of daily production.

Since the launch of FLIGHT DECK in 2024, OWS sites like the one in Shanghai have made meaningful progress, but this is only the beginning. FLIGHT DECK is about how — through the behaviors and fundamentals — GE Aerospace works to deliver for its customers. Behaviors create and reinforce the lean mindset, and the fundamentals provide the path to ensure safety, quality, delivery, and cost (SQDC), in that order.

Guided by the FLIGHT DECK behaviors, individuals like Wang seek out opportunities to improve how teams work and deliver for customers. Whether in Pudong, Shanghai or Cincinnati, in offices, workshops, or at airline field sites, they work to better serve customers and improve SQDC day in and day out.

The Shanghai flow line model has been so successful that it will soon be adopted by the Cincinnati OWS facility. And Wang will soon visit the OWS site in Seoul to discuss new plant standards there.

“Under the guidance of FLIGHT DECK, we are undergoing profound changes in both mindset and behavior,” Wang says. “This transformation not only allows engines to ‘flow’ but also energizes our team’s thinking, making operations more efficient. We are committed to continuous improvement through FLIGHT DECK, creating greater value for customers, lifting people up, and bringing them home safely.”

*The LEAP engine and the CFM-56 engine are manufactured by CFM International, a 50-50 joint company between GE Aerospace and Safran Aircraft Engines.