The Power and the Glory: GE Aerospace Delivers 3,000th GE90 Engine

September 12, 2023 | by GE Reports

In the annals of engine production, the GE90 holds a special attraction for both the aviation world and the people at GE Aerospace who’ve worked on the engine program. Among commercial engines, the number of firsts it’s chalked up over the years is hard to beat: First to enter service with carbon-fiber composite fan blades. First certified at over 100,000 pounds of thrust. First engine certified for ETOPS (Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards). First certified with an additive part. First program to employ analytics-based maintenance. First to use GE 360 Foam Wash.

Now the GE90 program can add another milestone to that list: delivery of its 3,000th production engine.

Still, when it was introduced in 1990, the GE90 wasn’t necessarily fated to succeed. “It’s kind of an epic story,” says Nate Hoening, GE90 program manager. “If you go all the way back to the early 1990s and consider the risks that leaders like [then GE Aviation president] Brian Rowe took to get the original version of the GE90 launched, it was an incredible bet on the future of air travel that airlines would go from four-engine wide-body aircraft to two-engine wide-body aircraft.”

On August 22, the GE Aerospace crew in Durham, North Carolina, celebrated the delivery of the milestone 3,000th engine.

On August 22, the GE Aerospace crew in Durham, North Carolina, celebrated the delivery of the milestone 3,000th engine.

Rowe believed in Boeing’s concept that large jetliners flying long-distance international routes could be powered by two engines — rather than four, as was typical — reducing both fuel and maintenance costs. But getting there meant supersizing the engines and developing parts from materials never used in civilian aviation before. “The GE90 will be the engine that will lead the way to the 21st century,” Rowe said.

The engine was certified by the Federal Aviation Administration on February 2, 1995, and officially entered service with British Airways in November 1995. However, by 1998, GE was behind in a competition with Rolls-Royce and Pratt & Whitney to power the Boeing 777. Some key airlines thought the GE90 was too expensive and its technology too risky to power passenger jets designed to fly over vast distances with only two engines. The poor market demand led GE to delay certification of the next variant of the engine. At one point, then CEO Jack Welch was said to have declared, “The GE90 is dead, put a stake in its heart.”

Suffice to say things did not look great for the program. “Many thought that it wouldn’t even fly again,” says Hoening. But in 1999, Jim McNerney, who was president at the time, doubled down. First, the engineers designed a more capable compressor for the GE90. Then, armed with positive reviews about increased fuel efficiency from operators in the field, McNerney and his team went on a sales offensive, generating enthusiasm among potential airline customers for a new variant that would achieve 115,000 pounds of thrust. More thrust meant the engines could carry larger payloads longer distances. After months of intense negotiations, Boeing finally agreed to make the GE90-115B turbofan the exclusive engine for its longer-range 777-300ER and 777-200LR jets.

The GE90 team at Batesville, Mississippi, celebrates the 3,000th delivery.

The GE90 team at Batesville, Mississippi, celebrates the 3,000th delivery.

“Ever since it went into service, the performance of the engine has been phenomenal,” says Hoening. “It’s become the standard for all wide-body engines. So the fact that it started off with so many bumps — to have it progress, to have it mature, and then to have it become effectively the first generation of a long number of GE engines that have been based on its design — it’s just incredible.”

Indeed, the architecture and mechanical design of the GE90 — from its carbon-fiber composite fan blades to its use of 3D-printed additive parts — has influenced every GE and CFM turbofan over the past two decades, including the GEnx, CFM LEAP,* Passport, and the next-generation GE9X engine for the Boeing 777X.

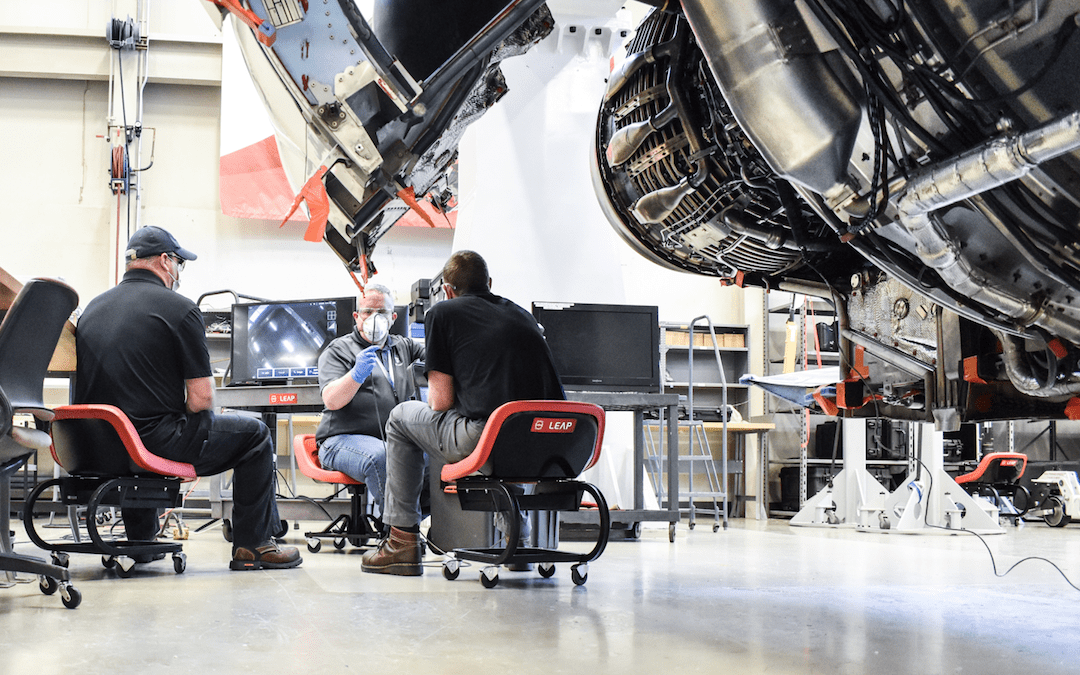

Hoening credits the introduction of analytics-based maintenance in particular as a “game changer” in terms of helping customers improve the “time on wing” of their GE90 engines. “With a normal aircraft, you schedule maintenance in an overnight window. With a GE90-powered 777, there’s never an overnight window,” he says. “You’re always flying overseas from one place to the next, where you have a couple-hour layover and fly again. So the reliability and durability of these products has become so much more important.” Working closely with the airlines to monitor the engines on a 24/7 basis “helps make sure that they’re proactive” when it comes to timing repairs and engine overhauls. “By doing that, we’ve been able to learn more and help keep the majority of engines on wing, because we use the data to actually drive the maintenance,” he says.

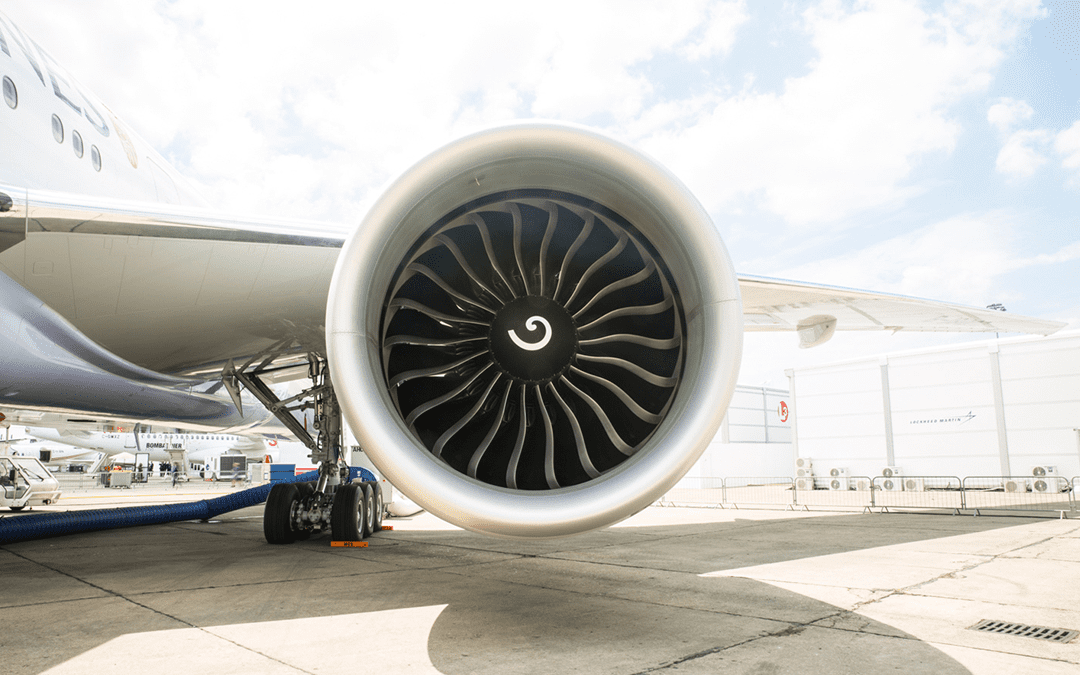

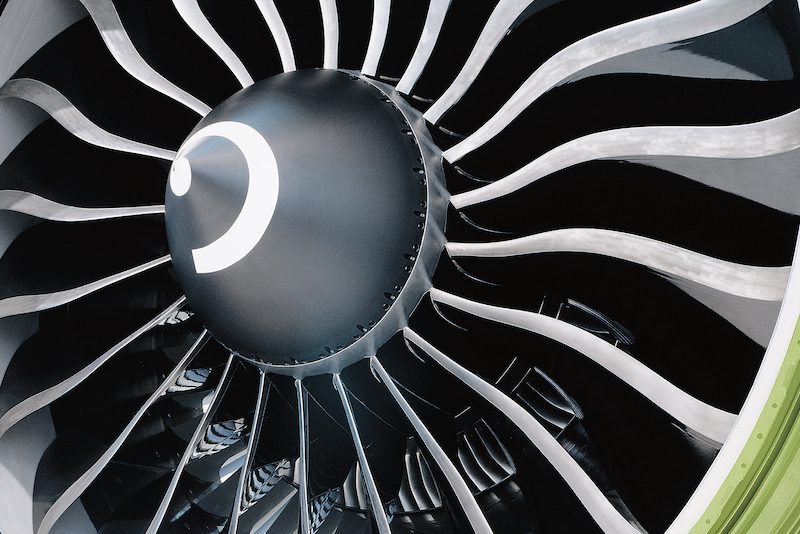

A close-up view of the GE90, with its 22 four-foot-long swept fan blades. Each carbon-fiber composite blade weighs a mere 50 pounds.

A close-up view of the GE90, with its 22 four-foot-long swept fan blades. Each carbon-fiber composite blade weighs a mere 50 pounds.

In addition to analytics-based maintenance, Hoening notes that the redesign of four main components in the combustor (the “hot section” of the engine) in the mid-2010s, followed by the introduction of 360 Foam Wash to clean GE90 engines flying regularly in hot and harsh climates, led to a significant increase in fuel efficiency and durability, and a reduction in carbon emissions. “The combination of those three technological advances really moved us from an average of 2,000 cycles [combined takeoffs and landings] prior to engine removal for maintenance to averaging well over 4,000 cycles now, with some engines over 5,000 cycles,” he says. The GE90 engine program currently has a dispatch reliability rate of 99.98 percent, with 29 engines individually logging more than 100,000 flight hours.

Hoening sees sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) as the next big step in further reducing the GE90’s carbon footprint. Earlier this year, a Boeing 777-300ER operated by the airline Emirates completed the first test flight in the Middle East and Africa using 100% SAF to power one of its two GE90 engines. “With a lot of these wide-bodies, sustainable aviation fuel will be a big part of meeting sustainability goals,” he says.

In terms of reliability, another factor working in the engine’s favor is the fact that more than half of the GE90s currently flying are less than 10 years old. And airlines are stepping up efforts to convert older passenger jets into freighters. “We’re working with a lot of those conversion houses, lessors, and freight operators [to see] how the GE90 can continue to support their operations as they take 15-to-20-year-old airplanes and plan to fly them for another 20 to 25 years,” Hoening says. “A lot of these engines still have a long life ahead of them.”

As FedEx takes delivery of the 3,000th GE90 this month, Hoening looks back at the program’s long and sometimes bumpy history with admiration. And he’s not alone. “One of the things that amazes me is the legacy of leaders that were involved in the GE90,” he says, before ticking off a list of names that include Rowe, McNerney, former GE90 program managers Russ Sparks, Chaker Chahrour, and Bill Millhaem, and former GE Aviation CEO David Joyce. “Talk to anybody who’s been involved in the GE90 and it’s almost like their eyes light up.”

For Hoening, that feeling has never gone away. “I definitely have a soft spot in my heart both for the people that have worked on the program as well as for the engine itself,” he says. “I still love sitting on a 777-300ER and hearing it start up. It’s an amazing sound.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IiIduF7QmM0&t=175s

*CFM International is a 50-50 joint company between GE and Safran Aircraft Engines.