Ready to Go: When the U.S. Navy Needs Help Getting a Jet Airborne, Scott Fitzgerald Is All In

September 5, 2025 | by Dianna Delling

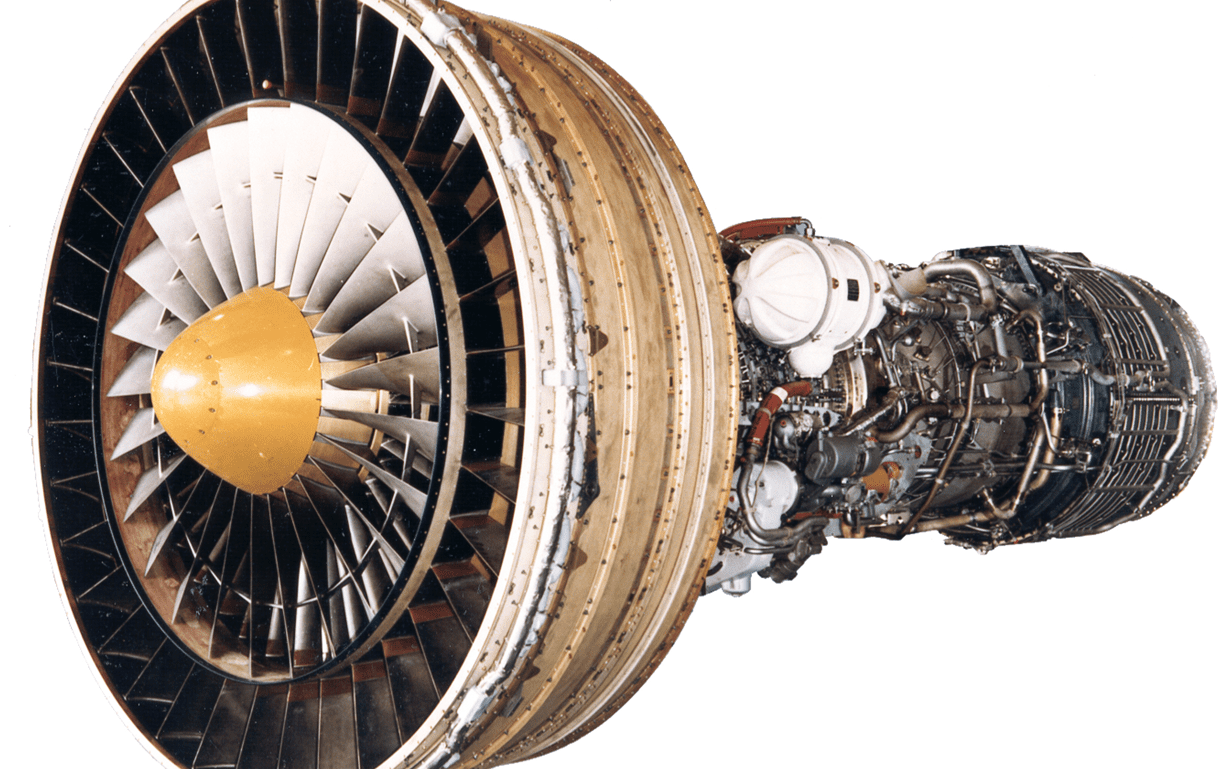

The sight of aircraft flashing through the skies above Virginia Beach, Virginia, is a good sign that things are humming right along at U.S. Naval Air Station Oceana — although roaring might better describe life at the busy base. Oceana is home to 16 squadrons of F/A-18 Super Hornets, supersonic military jets that provide combat airpower for the U.S. Navy. The planes, each powered by two GE Aerospace F414 afterburning turbofan engines, can accelerate from zero to 300 miles per hour in seconds, and they’re constantly on the move, flying up to 600 training and testing sorties each day to remain combat-ready. So if things got quiet on the airfield, Scott Fitzgerald would take notice.

Fitzgerald, a senior field manager at GE Aerospace and a U.S. Air Force veteran, is a go-to expert for F414 engines, and he’s embedded with the sailors at NAS Oceana to ensure they have everything needed to keep their planes in the air. Leading a team of six customer field service representatives (CFSRs) that serve naval squadrons along the East Coast, he’s always on call to provide technical advice, handle hardware-related needs, or run training workshops for military technicians. That includes jumping in to troubleshoot — quickly — when an F414 engine is grounded, whether it’s flying from a land base or the deck of a ship. When planes are deployed to global hot spots on aircraft carriers, a CFSR will often embed on the carrier, too.

“We are all in when they need us,” says Fitzgerald. “We work side by side with the customer, rolling up our sleeves, finding answers, and making sure we get it right the first time.”

Living in a perpetual state of readiness is second nature to Fitzgerald, who served 24 years as an Air Force propulsion systems specialist before retiring in 2019. “There’s an adrenaline piece in the fact that we’re trying to diagnose a jet engine that’s about to power an airplane at Mach 1.5, and it’s just such raw power,” he says. “That’s why I’m still, to this day, enamored with what we do.”

Technical Expertise — and Straight Answers

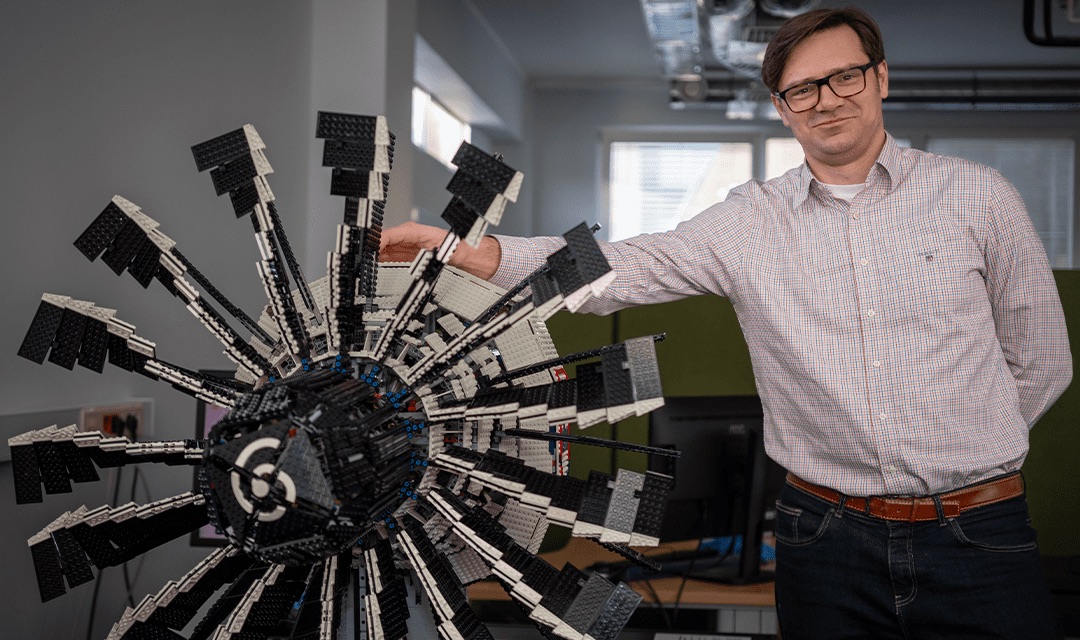

Fitzgerald joined the Air Force after high school, following in his older brother’s footsteps. Unsure of a career path, he signed on for the military’s Aerospace Propulsion technical training program mainly because he’d enjoyed “tinkering with things” as a kid growing up in New York and New Jersey. He realized he’d made the right decision once he started his first assignment, as a technician servicing engines for B-52s at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. After five years at Barksdale, he worked on bases in Germany, South Carolina, and the United Kingdom, gaining technical experience on a variety of major combat engines, earning his MBA, and becoming a fan of Premier League soccer along the way.

By 2019 Fitzgerald was working with Air Combat Command at Joint Base Langley-Eustis in Virginia, overseeing propulsion programs for Air Force combat fighter planes. It was a prestigious, senior-level position, but after more than two decades of service, he was ready for a transition.

“As I came up through the military ranks, I looked at our customer services reps as the technical experts we could always go to,” he says. “Before making any major decision I would consult with them to make sure I was getting a straight answer. Sometimes people who work for you will tell you what you want to hear, but I wanted the truth, good or bad, so I could make an informed decision.”

Time and again, as he chatted with his reps, he recalls, “I thought to myself, I can see myself in that chair one day. And here we are.”

Fitzgerald began his GE Aerospace career as a logistics manager supporting F414s. But in 2020 he saw an opportunity to move into a role as lead field services representative, and three years later was promoted to senior field service manager.

The Story Is in the Data

When Fitzgerald and his team evaluate an engine’s performance, they tap into its flight file, a comprehensive collection of data recorded moment by moment. By looking closely at things like fuel flow rate or component temperatures, they’re able to spot trends or abnormalities that help pinpoint the source of a problem, sometimes even before it begins to affect operations.

“The story is in the data,” Fitzgerald explains. “When you get smart at reading the data, you become really effective at isolating what’s going on with a propulsion system.”

The same principle holds true for business operations, although customer service interactions can be harder to quantify than engine outputs. So Fitzgerald has been using FLIGHT DECK, the proprietary lean operating model introduced by GE Aerospace last year, to develop a robust operations tracking system for his team.

With the help of other FLIGHT DECK leaders in the company, Fitzgerald has established a set of key performance indicators that help put the CSFR’s daily work into perspective — things like response times and details about each customer service request. Over time, the data can help the team spot process inefficiencies and flag quality control issues, guiding them to provide more efficient service and potential cost savings for both customers and GE Aerospace. “FLIGHT DECK is helping us break down what we do as a whole and make sure we leverage what we learn across the rest of the organization,” he says.

Fitzgerald has two sons who serve in U.S. Army aviation units. His daughter went in another direction — she’s currently studying wildlife biology in college — but she clearly appreciates her father’s accomplishments.

“Do you ever wonder why people are so intrigued when you tell them what you do?” she asked him recently. “It’s because your work is cool, Dad!”

Fitzgerald concurs. “At the end of the day, when I step back and look,” he says, “I think this might be the best job in the world.”