A friend in high places: New GE Company aims to ease drone industry's growing pains

June 7, 2018

By Fred Guteri

Think of all the work that drones could be doing right now. They could be fighting Zika-carrying mosquitos in Florida, inspecting gas pipelines in Alaska and checking the structural integrity of bridges and dams across the country. They could be rushing medical supplies to the scene of accidents, carrying people to the airport and yes, even delivering pizza. Drones — or unmanned aerial vehicles, as they’re called by people in the industry — are a revolution waiting to happen.

Before the revolution arrives, however, people operating aircraft without a human pilot inside and regulators have some work to do to make sure manned and unmanned air traffic can share the skies safely.

That’s because current air-traffic rules are highly restrictive for drones. The airspace below 500 feet, where most UAVs live, bristles with power lines, trees, buildings, bridges, airplanes landing and taking off — and people. Flying a UAV over 55 pounds, or at night, or flying over people and flying beyond the visual line of site — say for inspections — are currently prohibited. Any company that wants to fly those types of operations must apply for an exemption from the Federal Aviation Administration. This process entails spelling out in exacting detail the operation and every possible contingency — what if a plane aircraft enters the airspace, or a person, or a rotor fails, and so forth?

To be sure, dozens of guidelines already exist to keep safety in the sky the focus, but at the moment, few people understand the process for adhering to them. Meanwhile, the requests for FAA exemptions are pouring in. “We’re working on a project in Texas that calls for a drone that weighs more than 55 pounds to fly out of the line of sight of its operators,” says Ken Stewart, general manager of AiRXOS, a new GE subsidiary that offers support services for the drone industry. “That’s precedent setting.”

Indeed, drones are so new that projects often set precedents. For the drone revolution to get off the ground, the approval process needs some streamlining, and that’s where AiRXOS comes in.

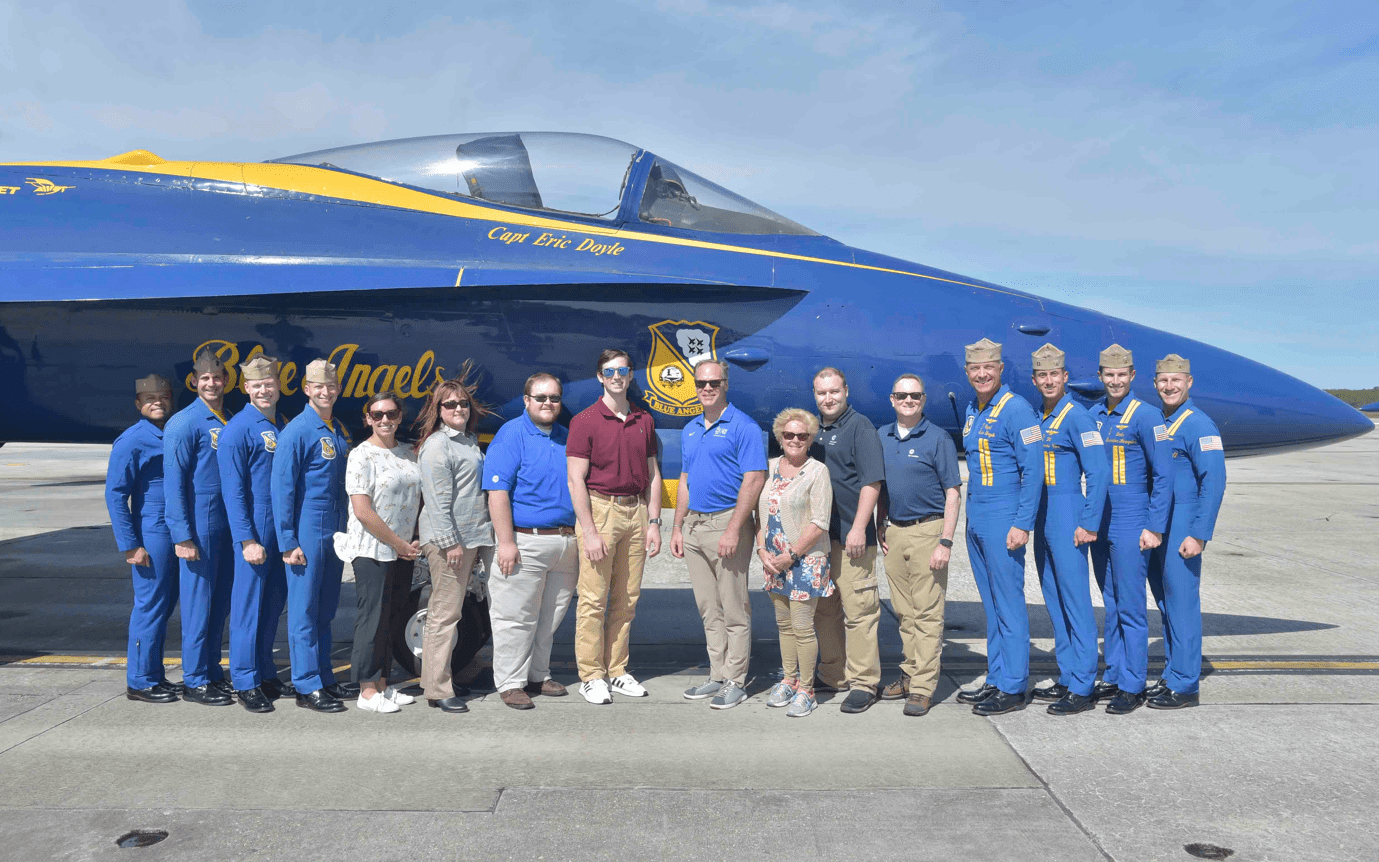

We need an air-traffic control system for drones, says AiRXOS CEO Ken Stewart. Top and above images credit: GE.

Some background first: Demand for UAVs has surged in recent years. With 7 million drones expected to be sold by 2020, the current air traffic management systems can’t scale to the predicted drone density. They also aren’t readily adaptable to drones. Pilots communicate to air traffic towers and use radar for detection to avoid mishaps. Not so with drones, which don’t have an on-board pilot and fly close to the ground, where they can’t use radar.

As federal regulators start to catch up with the glut of drones, companies like AiRXOS are trying to smooth out the process of building traffic management systems for UAVs and help cities, states and local governments establish their own UTM systems. What is a UTM? It’s complicated, like anything in this field. The abbreviation actually stands for a compound acronym — yes, there can be such a thing — meaning Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Traffic Management. More simply, UTMs spell out the rules that prevent drones and aircraft from colliding with each other.

AiRXOS combines hardware, software and services to provide the infrastructure of a UTM, allowing it to coordinate every element of the system, including weather and obstacle information. Before you fly, AiRXOS provides an automated certification and waiver service that allows UAV operators to obtain all the approvals and clearances necessary for using a particular airspace, as well as the technical support to establish operations. It will advise on how to fill out FAA forms and make risk and safety assessments.

This will happen manually at first, but AiRXOS will eventually make this into an automated, cloud-based service. “People can come to us and say, ‘Here’s what our applications looks like. How can we submit it to the FAA?’ ” Stewart says. AiRXOS will be deploying this service in Centerstate, New York, and plans to open an office in the Syracuse Tech Garden.

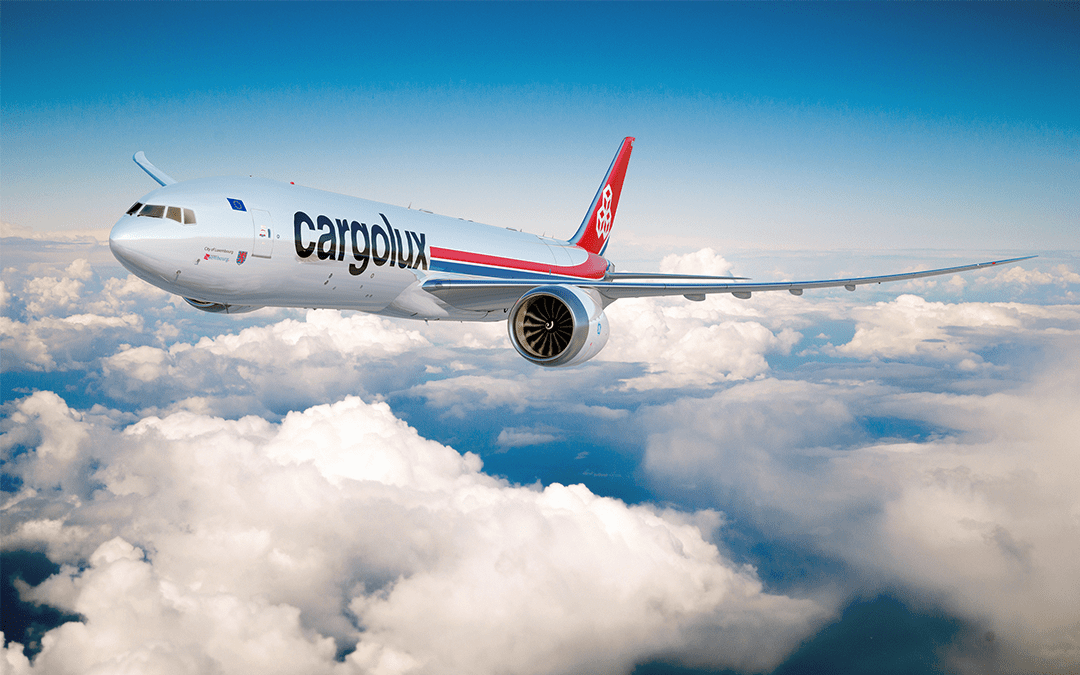

Flying a vehicle over 55 pounds, or at night, or flying over people and flying beyond the visual line of site — say for inspections — are currently prohibited, and any company that wants to fly those types of operations must apply for an exemption from the Federal Aviation Administration. Image credit: iStock.

If the idea of regulating drones to such an extent seems daunting, remember that the airline industry was once in a similar situation. It could not have gone from flying machines made of bicycle parts to jets that crisscross the globe every day without the establishment of regulations, standards and technologies for communications and tracking. “We need something similar for drones — an air-traffic control system for unmanned vehicles,” Stewart says.

The Department of Transportation and the industry took a step towards establishing such a system in May, when it invited proposals for drone projects in 10 U.S. airspaces. The idea behind the pilot programs is to establish operational experience in a range of different situations that can ultimately inform standards and best practices. Of the 10, AiRXOS was selected for three projects for San Diego, Memphis, and Choctaw Nation.

For instance, in the airspace around Memphis, Tennessee, AiRXOS, FedEx and several UAV firms will work on using drones to inspect airport runways for debris. Some drones may use laser imaging to detect debris; others may use high definition cameras or thermal imaging. They will also experiment with different types of communications networks to keep tabs on the UAVs. In other projects in Memphis, drones will monitor the security of the airport perimeter, deliver airplane parts at a nearby FedEx facility, and inspect farms, rivers and the Liberty Bowl Memorial Stadium, the home of the University of Memphis Tigers team.

By mid-2019, Stewart expects AiRXOS to be well under way with several projects in Memphis, and also in San Diego and the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma. Making drones as routine as airplanes will take a few years more.

This article was originally posted on GE Reports.